Archive for January, 2011

Web Maps: Try Hard and Mind the Style

*This article was originally posted on 1/24/2011 on GISUser.com. I’ll be writing a monthly expert column there. Woohoo! The link to all my columns (only 1 so far) is here. In this column I try my best to sound like I know what I’m talking about, re: web map design. There’s a big audience for web map design concepts but I’ll only be able to cover the basics as I’m not completely schooled in this area. Please help the readers by commenting if you’ve got some tried-and-true design ideas!

You know the old stock character of a writer hunched over a typewriter, balls of discarded drafts cluttering up the desk? Web map designers need to do more of that. We need to be editing our web mapping projects with as much fervor as an author. Perhaps then we can design web maps with a perfect balance of simplicity, usability, and knowledge transfer – or at least try to get closer to perfect.

Half of the problem is that lack of effort, the other half is a lack of good designs to emulate. Web maps have so many benefits over the traditional paper map but design principles for them are very new and still evolving. However, enough years have passed for cartographers to now understand what doesn’t work (long load times and trying to recreate GIS software on the Web are just two examples) and what does work (fast, informative, real-time). Speaking just from the aesthetic design point of view, which includes usability, there are some emerging elements of style that are effective and worth trying in your next project. Two of them are covered here.

The first is to steer away from what used to be the staple web map design element: the clickable table of contents holding every conceivable data layer that an organization produces. It’s not just slow and clunky, a lot of users don’t even know how to use it. On small screen mobile devices the table of contents is almost impossible to deal with.

How do you present multiple layers in an intuitive way, then? Take a look at www.govmaps.org. Each type of information gets its own thumbnail map – think highly visual and intuitive – that, when clicked, goes to a web map that contains just the layers pertinent to that subject. Now, if presenting all the layers on one map is something that the users just have to have, then try listing the layers in an integrated drop-down menu like on http://innovista.sc.edu/map/.

Another new style technique is to utilize click and hover capabilities in place of traditional annotation. Annotation that gives the user an instant location awareness (“USA”, “Spain”) is still okay. Annotation that provides details about data points, however, is often better served up upon a mouse click or mouseover in order to keep the original map visually uncluttered and more interactive. For example, the map for this business (yes, it’s pink!) gives you a small picture and name of a few places you might be familiar with that are nearby, but only via a mouseover: http://odopod.com/contact/.

By paying attention to newer and better style techniques such as these and by ruthlessly “throwing away” or editing early drafts, web map designers can vastly improve our work products. Perhaps then we can avoid being admonished in the way of my former boss who would sometimes exclaim, “of all the unmitigated audacities!”

Map Exaggeration

Posted by Gretchen in Best Practices on January 27, 2011

A few types of map exaggeration:

- Area features with thick outlines

- Points, if you were to measure them at the scale of the map, that are much larger than the thing they represent

- Raster grid cells that represent points, where the points are smaller than the grid cells

- Vertical height multiplied by a factor of two or more on 3D maps

Mapping a large geographic area with a few small, spread out area features in it, is a prime reason to use map exaggeration techniques. In order to allow them to “pop” or have the right amount visual heft in comparison to a large surrounding empty space, it’ll be imperative to exaggerate their size in comparison to the other features. If you have 4 golf courses delineated that you want to show within a large county, they won’t be very visible unless you utilize exaggeration. Similarly, a 3D map of road steepness over a large geographic area may not adequately emphasize the hilliest areas unless the entire elevation surface is exaggerated.

In these cases, it is necessary that a note be made on the map to the effect of, “Golf course areas are not to scale,” for example. If the map could easily be misinterpreted and the audience will only be giving it a quick glance, then this note needs to be front-and-center. Otherwise it can reside in a less conspicuous location.

One instance when it is not absolutely necessary to state this caveat is when using map points to represent points on the landscape. Casual map readers and experts alike understand that small dots on a map are general location visualization devices and not to scale, therefore there is no need to explicitly state it. (In some cases, however, in maps such as the famous – infamous? – space-junk map, it would be wise to mention it.)

There is no one who does not exaggerate! ~ Ralph Waldo Emerson

Bring on the Critics

There has been some criticism of GIS Cartography: A Guide to Effective Map Design, all from academic-types, who contend that the book does not provide enough references to cartographic literature. I’d like to respond to that here:

If cartographic literature were compelling enough to cite then why has GIS cartographic design been so LACKING for all these years?

Okay, so there is some useful information in the traditional cartographic literature that would serve the GIS professional but they obviously aren’t getting the message. Why is that? Maybe a different mode of communication would be helpful, I said. Maybe a more been-there, done-that approach would be more successful. Maybe an intuitive system by someone who knows what it is like to try to make maps on their own would have more appeal. And those were the ideas I kept in mind throughout the research and writing phases of the book creation process.

For those in the trenches of map-production this book has useful advice that makes their jobs easier and makes their products better. If there had been such a book 12 years ago, my own initial cartographic attempts would have been much more successful.

Beginning a Cartography Project, Part 3: Colors and Type

Once the audience for the map is considered (see Part 1 of this series) and a sketch map is made and agreed upon (see Part 2 of this series), it is time to further the planning of the overall look and feel of the map by deciding on a color scheme and typography.

Color Scheme

Before you begin creating a color palette for the map with wild abandon, first find out if there are certain colors that must be used on the map. The first possibility is that the map should have colors that represent the company for which you are making it. For example, the Trust for Public Lands has an exact green color that they want to have on most of their products. You’ll need to get the specifications for that green color before designing a map for them. In this example the green hue is not something that has to be incorporated in the map itself, but rather needs to lend the overall layout the TPL signature look – so it is most useful as a border or background color to the entire layout.

The second possibility is that certain data layers on your map need to be represented with a particular color palette. For example, a geology map would need standard geologic colors and a soil age map could utilize a standard soil age palette. Furthermore, the usual standards regarding feature type and color will still hold true: blue for water, red/brown/black for roads, and so on.

Even if you are constrained by some of these color limitations, there will likely be features and elements that you need to create your own colors for. Begin creating your palette by compiling color swatches (I use PowerPoint for this, of all things, but any easy to use graphics program or even your GIS would do) for the colors that are required. Round out whatever there is left to render by picking and choosing colors, matching them with the colors you already have, and figuring out what looks good together. Don’t forget to consider the mood of the piece (loud or soft) as well as accent and background colors. I like to use a generic map in the GIS to populate the colors with so I can make sure they look good together in map form too.

Typography

Choosing the type for your map is much easier than choosing the colors if there aren’t a lot of annotation levels involved. The more annotation levels that you have (think 6 different city/town label groups) the more trouble you will have picking typefaces that have enough variation to capture the different levels while still allowing a cohesive look.

If you do have a lot of annotation levels then pick a typeface with a lot of flavors (e.g., oblique, italics, roman, bold, extra bold). As with colors, always ask your client if they have a corporate typeface that they would prefer you incorporate. Even if you don’t use it in the main map, you could use their typeface for the title and margin elements.

Initial Design Phase = Complete!

Well, that’s it. That’s all there is to the initial design phase. It’s a lot of upfront work and it isn’t your usual fumble-through it using intuition approach. With your audience on board from the get-go they’ll have more buy-in with the finished product. With a sketch map you won’t have to do many on-screen layout changes as you enter the build-phase. And with a design-board of colors you’ll have a template for your next cartography project.

Beginning a Cartography Project, Part 2: Sketch Maps

Once the audience for the map is properly investigated (see Part 1 in this series) it is time to consider the look and feel of the map. This part is going to depend a lot on what kind of map you are making: web map or static (paper) being the biggest two types. Regardless of what type of map, however, it is a good idea to start with sketch maps of potential layout designs.

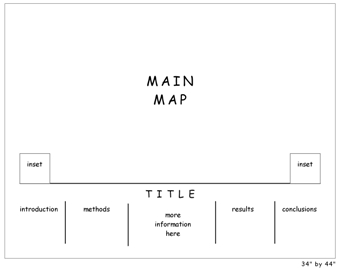

These sketch maps work best when they are drawn by hand so that technology doesn’t get in the way of the design. When presenting to test-audiences you can always move these into a digital medium like the one shown above after sketching them by hand.

The sketch maps force you to consider which layout elements will be needed to support the map before getting too steeped in their details. For example, while sketching you may create an area for a legend, north arrow, and data source descriptions but you will be thinking about how they look in relation the larger design instead of wondering which data sources should be cited, how to design the legend, and so on.

The sketch map helps designers of web maps, in particular, in that it allows the web map designer to quickly and efficiently try out novel presentation methods (of which there is still a lot of room for growth in this medium). For example, many of our developer colleagues feel that traditional web maps that mimic GIS software by including clickable legends do not make sense to casual web users. A web user who views your web map may be better served with an entirely different approach. The sketch map is the place to start if you want to create and visualize new approaches for conveying legend information.

If you are working on a print design / static map project, the sketch map should be mindful of the shape of your geographic area. Is the area you are mapping oblong, rectangular, square, or oddly shaped? Does this affect where you will place the margin elements such as north arrow, scale bar, and legend?

Author Pedestal?

Posted by Gretchen in Inspiration on January 18, 2011

In the book I wrote about how modern maps need to have authorship information such as the author’s name, perhaps their affiliation, website, or other contact information. I stress that this is secondary or tertiary to other aspects of the map in that it only needs to be seen by those who look for it. Therefore it should remain unobtrusive in the overall design.

Tufte talks about how important it is for an author to place his or her name on the map, not just the organization’s name. The idea is that this holds the author accountable and ostensibly will result in a better product.

The 16th century cartographers took this concept to a completely new level, however. This authorship pedestal is found on a map by Augustine Herman Bohemiensis in 1670 of Virginia and Maryland:

Just for fun, I wondered what it would look like if we used authorship pedestals today:

I sent my authorship pedestal to a long-time client the other day, as a joke, to inform him that all my maps for him will now bear this insignia. His response was that the pedestal should be higher.

Recent Comments