Archive for category Best Practices

5 Ways to Make Your Maps Better

Posted by Gretchen in Best Practices on April 1, 2011

- Surround all of the elements with boxes. This includes the legend, north arrow, scale bar, title, inset map(s), and any descriptive text you may have. The more boxes the better because they give the layout structure. The average map reader can’t figure out on their own where the legend ends and the map begins, for example.

- Ensure that the logos of all participating agencies and companies are placed prominently, preferably at the top, in a line. It’s okay if they are different sizes and shapes and colors. It’s okay if they clash with the rest of the map colors.

- Only spend, at most, about 30 minutes designing the map. Any more time than this is wasted. Good design does not take time, it only takes talent.

- Think a lot about what you want and need on the map rather than on what the map reader will want and need.

- Make sure the background (hillshade or orthophoto, for example) is displayed fully saturated so that it can adequately compete with the other map layers.

April Fools!!!

On Putting Boxes Around Elements

Posted by Gretchen in Best Practices on March 28, 2011

Putting an “organizing” box around all the elements on a map layout add unnecessary clutter and distracts from the map elements. If you must have separators between elements then use less obtrusive ones like a series of dots. The second map shown here illustrates how big a difference the map layout can look when you take the boxes away.

Map Display Location, Location, Location

Posted by Gretchen in Best Practices on March 16, 2011

We should be thinking not just about the effectiveness of our cartographic products in terms of what they look like and how well they transfer information, but also in how often we get them in front of the right readers and where.

We just got back from a short trip to Breckenridge where my kids and husband went skiing*. They told me that the lifts have maps that show up in front of you while you ride the lift, attached to the safety bar. What a great idea! This way you don’t have people trying to get their paper maps our of their ski coats, accidentally dropping them on the skiers below, or trying to hold them with freezing hands. You simply have the slope map right in front of you at the exact time when you need it!

Have you put some thought into how you can get your latest mapping effort in front of the most readers in the most convenient way?

*It seems I’ve had to explain this a million times lately, but I’ll give it one more go: I skied as a kid quite a bit and wound up hating it due to a long series of minor disasters that finally built up into an admonition that I will never ski again. So as an adult I took up snowboarding and, after two years of trying and never getting the hang of it, I finally gave up. The final blow was, well…a blow to the head, and I have never snowboarded again. It really isn’t worth paying $100 for a lift ticket to slowly glide down on my edge, on a green, all day. So instead of skiing, I read Donald Norman’s new book Living With Complexity and Ellen Lupton’s Thinking with Type. Both great reads!

Choropleth Legend Format

Posted by Gretchen in Best Practices on February 17, 2011

Earlier I posted about Choropleth Limitations. Choropleth maps have legends that show how the colors (or shades of gray, perhaps) match with the values they represent. There are a few different options for the presentation of these legends. In ArcMap, the legend defaults to a vertical style with the highest value (largest number) on the bottom of the list and the lowest value is at the top of the list like this:

I often prefer to push the colors together for a continuous color scheme like this by changing the ArcMap setting to 0 for “patches (vertically).” I also sometimes prefer to change the numbers to Courier New or some other monospaced typeface since numbers line up nicely when they are placed vertically. Like this:

However, I’m currently reading through a book by Daniel B. Carr and Linda Williams Pickle called “Visualizing Data Patterns with Micromaps” that asserts that the high value should be on top since that is how we are used to reading the y axis on graphs. This would change the legend to look like this:

I like to change it up occassionally and create a horizontal legend. I would think that Carr and Pickle would be okay with this since it reads from left to right the same way you would read the x axis on a graph, from low to high:

Choropleth Limitations

Posted by Gretchen in Best Practices on February 12, 2011

*This post was updated on 1/27/2016.

County level choropleth map of planted soybeans by area, created by PetersonGIS via some crazy USDA data wrangling efforts. This data and the associated geo-analytics (gathered for most of the country) were used as part of the inputs to a Colorado State University climate model.

Choropleth mapping, which shows the distribution of a variable within an enumeration unit, is a staple in every cartographer and GIS professional’s arsenal. However, it is always good to keep in mind the limitations of our tools, and the choropleth map does have some. These limitations are:

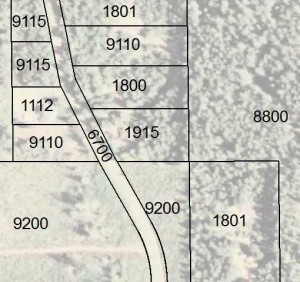

- The distribution of the variable is static at the scale of the map. No inference can be made about the variable at a more detailed scale. For example, the distribution of noxious weeds can be shown by state within the U.S. However, the distribution of noxious weeds within states (by county, perhaps) cannot be determined from a state map.

- It can look like the variable is constant across the unit, possibly resulting in map-reading failure. (Similar to above.) For example, if a state is colored red to denote a high level of noxious weeds, this may make the map reader think the entire state is over-run with noxious weeds when perhaps it is only one area of the state.

- The change between the enumeration units can appear to be quite crisp when in reality the variable is probably much smoother across those boundary lines. One state might be green for noxious weeds and a neighboring state could be red even though the counties on either side of the state line are more alike than different.

- Usually, you don’t show the actual value for the variable, you show the area-weighted or population-weighted value. This could be a limitation if a future map-reader wants to use your values for a different analysis or visualization because the raw data counts aren’t available, only the ratio values. We aren’t generally concerned about this limitation as cartographers, but if you feel like your data will be needed as raw data values in the future, the raw data could be supplied along with the map in a database or table.

- Make certain that your choropleth shows area-weighted or population-weighted data when needed (hint: almost always). For example, a map of TV watchers will probably resemble a population distribution map and should therefore be normalized by population such as the number of TV watchers in each county divided by the number of people in each county.

- The enumeration units may not have much to do with the variable. Noxious weeds probably have much more to do with land use and soils, for example, than with the state administrative boundaries.

- If your study units are of widely different sizes it can be difficult to show the color shading adequately in the smaller units. For example, in a map of U.S. states the smallest units – D.C., Rhode Island, Delaware – can be difficult to see. Some modern maps alleviate this difficulty by using hexagons as the enumeration units, with each hexagon signifying a state, for example. However, these are only useful for well-known geographic units like U.S. states or Admin 0 level data (countries).

- Related to the above point, misinterpretation can occur if a very large unit is colored brightly. If a large state has the same noxious weed / area ratio as a smaller state, and they are both colored bright-red, the larger state may appear to have a bigger problem even though the ratio is the same.

You may also be interested in these posts:

Your donation in support of this blog is very appreciated! It’s simple to make a donation with PayPal using my link.

I've updated my post on Choropleth Limitations. https://t.co/sI04IvvaI2

— Gretchen Peterson (@PetersonGIS) January 27, 2016

Nice post on choropleth limitations to keep in mind. https://t.co/2DGgzpMax5

— Alexandre Neto (@AlexNetoGeo) January 27, 2016

When is Complexity Okay?

Posted by Gretchen in Best Practices on February 8, 2011

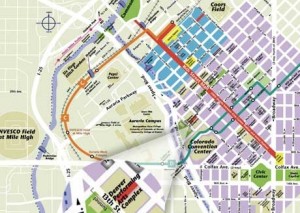

We often hear about simplifying and reducing in relation to map design. However, if you have enough time and patience to manipulate a lot of data layers and a lot of labels, you can make a complex map look good. So when do you know if your complex map is effective?

- When all the labels are legible

- When labels do not overlap

- When whitespace – or empty space – is still there

- When background and foreground are distinguishable

- When the colors are cohesive

- When there’s still a noticeable balance, either continuous pattern or strong focal point (see Map Balancing Tricks)

Recent Comments